The demise of cookies has been long foretold. Ever since they were invented in 1994, questions have been raised over their privacy implications and potential misuse; yet they have persisted, unloved but indispensable. However, it seems like the death knell has at last sounded for third-party cookies, with both Apple and Google finally taking concrete steps to rein in their use. But given that third-party cookies and mobile Ad IDs still underpin a huge amount of the web and its economics, what will life be like without them? And more importantly, will it actually be better than it was before?

To answer these questions, we first need to understand what’s actually going on in the world of third-party cookies and Ad IDs. I don’t know about you, but I find it pretty challenging to keep track of all the initiatives that the tech companies are trumpeting, and understanding what they might mean for users and businesses. Hence this piece, which aims to demystify some of this. But first, let’s remind ourselves of how we got into such a mess with third-party cookies in the first place.

How did we get to where we are today?

From the very earliest days of digital advertising, cookies were an essential tool for advertisers and publishers. They helped advertisers keep track of the number of people they were reaching with their ads; and they helped publishers understand their own audience. They also supported useful functionality like frequency capping (ensuring people didn’t see the same ad too many times).

As the industry grew and developed in the 2000s, new intermediaries such as ad networks, exchanges, and sell/demand-side platforms started to emerge to connect ad supply efficiently to demand, for whom third-party cookies proved similarly valuable.

For these intermediaries, the user data generated by these cookies, which included the ads they had seen, but also the sites they had visited, became a competitive differentiator, enabling ads to be sold based on the interests of the audience rather than the context of where they appeared. Bidding in real-time on ad inventory based upon the individual that was seeing the ad became the norm — so-called Programmatic Advertising. A complex ecosystem of companies providing services across this value chain grew up, and data itself became an important part of the industry, with companies like LiveRamp and Epsilon providing access to large pools of user data to use in ad targeting.

Meanwhile, Google and Facebook were building their own advertising ecosystems, leveraging the user data to which they had access. Google AdSense and Facebook Audience Network represent not only Google & Facebook’s first-party inventory, but also a large swath of third-party sites across the web, and enable highly targeted audience-based ad buying, all enabled with third-party cookies.

The result of this web of intermediaries is that whenever you visit a website or use a mobile app, your data is passed (or potentially passed) to a large number of different companies, who often then pass the data onto other third-parties, all to show you a somewhat more relevant ad (or show you an ad for that sofa you looked at 3 weeks ago on Wayfair).

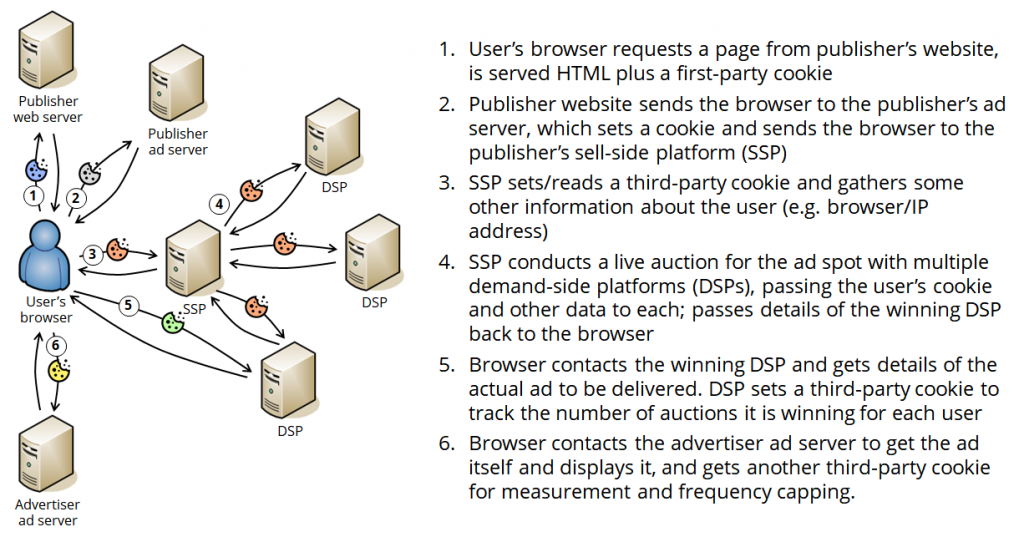

The diagram below shows some of the data and cookie flows involved in a typical programmatic ad call.

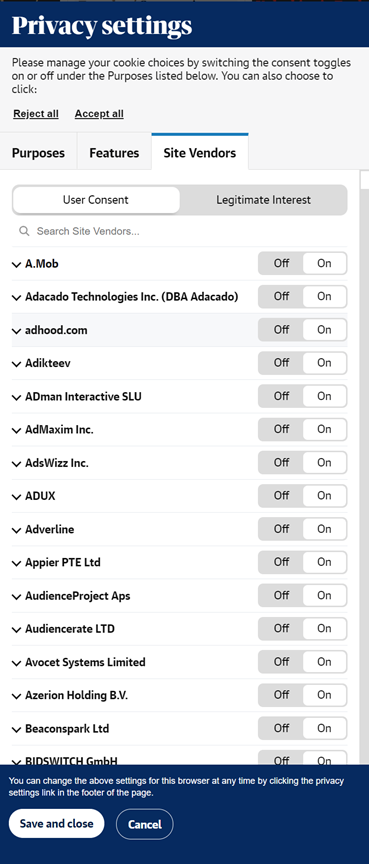

Until 2018 this third-party tracking and data processing was all going on largely behind the scenes, with sites not required to notify users or gather consent; but that changed in 2018 with the introduction of GDPR. GDPR requires organisations to gain explicit consent in order to process user data and pass it to third parties; but the trouble is, because of all the participants in the ad ecosystem, actually getting this consent is unworkably complex, as the example below from The Guardian’s website shows:

In response to this, Apple and Google have started to take a much harder stance on the third-party cookies and Ad IDs that support so much of this complex ecosystem. However, there are some pretty major differences in their approach, which reflect the fact that Google is a lot more dependent on advertising revenue than Apple is.

What’s Apple doing?

Apple has been pushing privacy as a differentiator for its products and services for several years. In 2017 it introduced Intelligent Tracking Prevention into WebKit (the underlying browser tech for Safari), which limits the ability for sites to send or request data from third-party sites, known as cross-site tracking.

The privacy issue that Apple sought to address with ITP is that a third-party ad service (such as a demand-side platform) that serves many advertisers and publishers can amass a large amount of information about the interests and behaviours of users — so-called “cookie pools”.

A simple way to block this kind of data collection would be to block all cross-site calls (and third-party cookies with them); but this would cause problems for many legitimate uses of this technique, such as Content Delivery Networks, or federated login. So the Apple ITP feature uses machine learning to detect which sites on the internet are being used for cross-site tracking.

In 2020 Apple further tightened ITP to block all third-party cookies. Sites can still use a Safari feature called the Storage Access API to request a specific opt-in from a user, but given that the user will need to have some good reason to agree to the third-party storage, this has essentially spelled the end of third-party cookies on Safari.

Apple ID for Advertising (IDFA) restrictions

Apple introduced the “ID for Advertising” (IDFA) back in 2012 as a way to persistently identify the device that an app is installed on. Any iOS app can access the IDFA and pass it to a service on the internet (such as an ad network). Because the IDFA is the same across apps, it works a bit like a third-party cookie; if App A passes the device’s IDFA to a third-party service, and then App B passes the same ID, then the third-party service knows that the user is using both apps.

Since its introduction, the IDFA has been enormously useful for Mobile Ad Networks, app publishers and measurement platforms to support measurement and targeting. For example, Facebook uses IDFA for enabling ad targeting in third-party apps in its Audience Network. If a user interacts with a lot of content about, for example, gardening in the Facebook app, a third-party app that uses Audience Network can use the IDFA to deliver ads about gardening to the user.

The IDFA is anonymous and can be opted out of, but its use contributes to the somewhat creepy sense that users have that their phones are listening in on their conversations. This is because an interaction in one app can drive ad targeting in another app which the user doesn’t associate with that interaction.

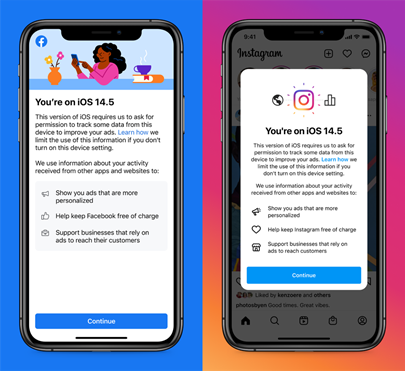

In April, Apple released iOS 14.5, which changes the use of the IDFA to opt-in – apps that want to capture the value and share it have to ask permission first. Facebook has made quite a fuss about this, even going to the lengths of creating a dedicated website to trumpet the value of targeted ads, and serving pop-ups in the Facebook and Instagram mobile apps to encourage people to opt in:

Despite these efforts, it is looking like opt-in rates for third-party sharing of the IDFA are pretty low — according to a recent study by Flurry, a whopping 96% of iPhone users in the US are choosing not to share their IDFA with third-parties.

What’s Google doing?

Google’s dependence on advertising as a major revenue source means that it has a much more complicated relationship with data and privacy than Apple; so it’s been a lot slower to introduce privacy features into its Chrome browser or Android mobile OS.

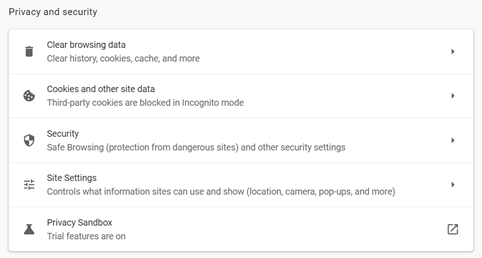

With all the noise about privacy that Apple has been making, Google couldn’t just sit by and do nothing. So January 2020 it announced that it would be phasing out third-party cookies in Chrome within two years. In their place, Google is creating an open-source initiative as part of the Chromium project, called Privacy Sandbox. Privacy Sandbox is a collection of technologies to enable a move away from third-party cookies while not encouraging advertisers to look for equally intrusive (and less transparent) alternatives, such as device fingerprinting. Privacy Sandbox is already live in the latest versions of Chrome (see below), though largely disabled in Europe.

The Privacy Sandbox project represents one of several initiatives being pursued by members of the W3C’s Improving Web Advertising Business Group, which for some reason all share bird-themed names such as TURTLEDOVE (from Google), PARRROT (from Magnite), SPARROW (from Criteo) and PARAKEET (from Microsoft).

FLoC and FLEDGE

The most advanced and high-profile of the Privacy Sandbox projects is called Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC), which aims to enable advertisers to deliver behavioural targeting without building cookie pools. FLoC parses the sites (and site content) that a user visits to place them in one or more interest-based groups (or ‘cohorts’), using a machine learning algorithm. A website can use the FLoC API to then discover whether the user is in a particular cohort and deliver targeted content. Because the profiling is happening within the user’s browser, no user-level information is sent to the internet, so third-party sites cannot build cookie pools or access the information directly. Through careful design of the segmentation algorithm FLoC aims to minimise the risk of reverse-engineering of user information.

With a related project, called FLEDGE, Google aims to enable publishers to create their own interest segments and then hold auctions for advertisers to reach those segments, but without passing user-level data. It’s pretty challenging to replicate all of the current targeting capabilities of the ad ecosystem without passing any user/device data; and indeed, in the latest iteration of FLEDGE (the above-mentioned TURTLEDOVE) Google falls back on a “trusted third-party service” to handle some of the real-time auction mechanics.

Google’s Privacy Sandbox, FLoC and FLEDGE all need to be properly in place and accepted by the web community and advertising industry before Google is likely to shut off third-party cookies in Chrome. Perhaps because of this, Google recently announced that it was delaying this shut-off until 2023.

Google hopes that other browser makers that use the Chromium open-source engine (such as Microsoft’s Edge browser, and Opera) will adopt the Privacy Sandbox features and implement their own versions of the algorithm; but enthusiasm is low, with none of the major browser-makers signing on. Brave, Microsoft, Vivaldi and Mozilla have all come out against FLoC, and have disabled it in their browsers that are based on Chromium. The reaction from regulators and other industry groups has been no more positive: The Electronic Frontier Foundation greeted the news about FLoC with an article entitled “Google’s FLoC is a Terrible idea“.

Criticism of FLoC centres around two major areas of concern:

It does not actually represent an improvement to privacy: FLoC replaces one set of poorly understood tracking technologies (cookies) with another (the FLoC algorithm and the data it stores in the browser). Furthermore, because the operation of FLoC involves the processing of personal data, European data regulators are considering whether user consent for the feature will be needed in order to comply with GDPR. In light of these concerns, Google has not yet enabled FLoC in Chrome in GDPR countries.

FLoC will further concentrate advertising power with Google: The combination of Chrome’s dominance in the browser market with Google’s 31% share of digital advertising raises the real risk that Google will exploit the information gathered by FLoC to grant an unfair advantage to its own advertising network. In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority has opened an investigation into whether FLoC represents an unacceptable concentration of power with Google’s advertising ecosystem.

Google’s Android Advertising ID

Android also sets an Advertiser ID, called the Android Advertiser ID (AAID), which users can opt out of; but Google has not announced any plans to introduce a similar opt-in control in the way that Apple has done. Privacy advocate Max Schrems — famous for giving Facebook a bloody nose more than once on privacy — has brought a complaint about this to France’s Data Protection Authority, CNIL, claiming that the behaviour of the AAID is a violation of GDPR. So Google may be forced to implement a similar consent mechanism to Apple’s, at least in Europe.

Impact to the Digital Advertising ecosystem

If you weren’t confused when you started to read this article about all the changes going on in the world of third-party cookies and Ad IDs, you probably are now. If it’s any consolation, the rest of the analytics and advertising community are pretty confused also. But given Apple’s actions and Google’s stated intent, it is fair to assume that the writing is on the wall for cookies and Ad IDs. But will this make things better or worse for publishers, advertisers and consumers?

Publishers

According to a study by Google (which one should therefore take with a pinch of salt), publishers can expect to see a revenue decline through the loss of user-targeted ads of 52%. However, another independent study predicted only a 4% drop in revenue. The true revenue impact is likely somewhere between these two estimates, but publishers will adjust their monetisation strategies to minimise the impact of losing user-targeted inventory, so it’s very hard to predict the true impact on content publishing businesses.

The trials and tribulations of the print media industry in the last 20 years, seeing their advertising revenues tumble as they moved online, is a well-known story. However, some of the ways that the industry has adapted, with its heavy focus on user-targeted ads, have not served it well, leading to ‘click-bait’ headlines that exist purely to draw traffic to the site in the hope that it will monetise (probably through a low-quality retargeting ad) once there. With a reduced ability to earn an ‘easy’ buck this way, publishers will need to focus more on generating real engagement with their content, which could be a good thing for the consumer.

Networks and “The Big 3”

As we covered earlier, Facebook made quite a lot of noise in the run-up to the IDFA opt-in change in iOS – but interestingly, Mark Zuckerberg subsequently changed his tune, acknowledging that the change could actually help Facebook by causing people to spend more time (and money) inside the company’s first-party apps. Facebook’s incredible trove of first-party data means that what revenue it may lose through its third-party network it may more than make up for on its own apps.

Google isn’t in quite such a good position as Facebook, but it still manages a very strong set of first-party data through Google Search, Gmail and other apps in the ecosystem, and can leverage its control of the world’s most popular browser. Even if only Google’s ad network supports the technologies in Privacy Sandbox, Google may actually be able to draw business away from independent platforms like Criteo and Taboola.

Another company in this enviable position of sitting on a lot of very rich first-party data is Amazon, whose advertising business is now nipping at the heels of Facebook and Google’s. Many users who are looking to buy something now go straight to Amazon to search for that item rather than bothering with a web search first, and can also offer advertisers end-to-end measurement and attribution, which its rivals cannot.

Advertisers

Many larger advertisers’ media plans have already become somewhat hollowed out by the emergence of Google, Facebook and Amazon as behemoths in the digital ad space, often consisting of little more than a few branded run-of-site/sponsorship efforts for brand recognition, paired with audience-based buys on Facebook, Google and a programmatic platform like Criteo. A further consolidation of audience reach and engagement in the hands of these companies could further distort this picture, leaving advertisers even more at their mercy.

Smaller advertisers (especially B2C advertisers), on the other hand, will likely become almost completely dependent on the “Big 3”, and thus dependent on their algorithms for pricing and displaying ads. The presence of three major competitors for ad dollars may at least provide some protection from price gouging, but it is hard to imagine any significant threat to this near-triopoly.

Consumers

Last but not least, will consumers benefit from these changes? This is a harder question to answer.

On the one hand, making it harder for organizations to silently track individuals’ online behaviours is a good thing for consumers, as when offered the choice of whether to share this data, they overwhelmingly opt out (as the Flurry study mentioned above shows).

On the other hand, there is a real risk that the death of third-party tracking will concentrate more power in the hands of Amazon, Google and Facebook. This is unlikely to deliver much benefit to consumers: it will reduce choice without significantly improving transparency around the use of their data, and anyone who wants to opt out will likely not be able to use these services in a meaningful way. And it’s not clear whether the technologies being proposed to replace the functionality of third-party cookies will really be any better for consumers; and they could prove more difficult to manage and opt into/out of.

As the last several thousand words of this post have demonstrated, the world of privacy and user data management is, if anything, getting more complicated, not less. Consumers may be getting more privacy-savvy, but if the tools they are offered to manage their personal data are too hard to use, they will not be well-served, and we’ll be back to square one.