Amidst all the craziness of the global coronavirus pandemic, it’s easy to forget that the world keeps turning, and that mundane things like new privacy laws coming into force are still happening. The impact of COVID-19 on global privacy practices is the stuff of a future post, but in the meantime, let’s distract ourselves with a little light reading about California’s new privacy law, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and how it compares vs GDPR.

If you and your organization are only now getting over the trauma of achieving GDPR compliance, you may be unenthusiastic to learn that there’s another privacy law to worry about. The good news is that if you’re reasonably good on your GDPR compliance, you should be well-prepared for CCPA. The bad news is, many US organizations haven’t done much to achieve GDPR compliance, so they’ll have a hill to climb to be ready for CCPA.

What is CCPA?

CCPA is only one of a handful of state-level laws in the US that have been approved in the past two years to protect consumer privacy. Since it comes from the home of some of the world’s largest and most data-hungry online firms, however, it has garnered the most attention. CCPA is also worth paying attention to because it is likely to be the template for any federal privacy law that is passed in the United States.

CCPA became law on the 1st of January 2020, and enforcement (by the California Attorney General) will begin on the 1st of July 2020 (apparently the AG is unmoved by pleas to delay enforcement due to COVID-19). This gives any business that operates in California, or interacts with California residents, a very narrow window to achieve compliance. A recent research study from Ebiquity in partnership with the Digital Analytics Association found that 22% of businesses in the US have not done anything to prepare for GDPR, leaving them in a scramble to prepare for CCPA.

CCPA vs GDPR

CCPA and GDPR share many things in common, based in the idea that an individual should have control over whether and how an organization collects and shares data about them, and that that data should be treated with care.

Unlike GDPR, CCPA does not attempt to define whether data processing is legal per se (except in some narrower cases like passing data to a third party). However, it does enable heavy penalties if a company is found to have failed to protect user data adequately, with potential fines exceeding even GDPR’s levels. Most of the fines imposed by European privacy regulators have been for breaches in data security, so it’s reasonable to expect the California AG will behave similarly.

The table below summarises the major areas of difference between GDPR and CCPA. Generally speaking, GDPR’s requirements in each of the areas are stricter than CCPA’s, although there are some exceptions. Below the table, we’ll look at each of the areas in a little more detail.

|

Area |

GDPR |

CCPA |

|

Legal basis for data processing |

|

|

|

Who’s regulated |

|

|

|

Who’s protected |

|

|

|

Data covered |

|

|

|

Individuals’ rights |

|

|

|

Privacy notices and consent |

|

|

|

Data retention and security |

|

|

|

Enforcement and sanctions |

|

|

Legal basis for data processing

The biggest difference between the two laws is how they approach the legality of data collection and processing itself. GDPR sets out the conditions under which data processing is allowed, such as that the subject has given their consent, there is a legal obligation, or the Data Controller has a ‘legitimate interest’ to process the data.

If a Data Controller (such as a business) is processing personal data without one of the above conditions being met, then they are in violation of the law, regardless of whether there is any data breach or complaint from users.

Under CCPA, a business must disclose information about the data that they are collecting about a consumer, and offer users the right to view or delete that data, but pre-emptive consent is not required; additionally, CCPA enables consumers to opt out of having their data shared with third parties.

If a consumer feels that their data is being misused, they can bring action against a business. But CCPA does not define whether a particular usage of data is legal, and has nothing to say about secondary usage (that is, collecting data with one stated purpose and then using it for another purpose) outside of requiring the business to update its privacy notice.

Who’s regulated, and who’s protected

CCPA uses the term Business to describe the entities that are the subject of its regulation, defined as any for-profit organization doing business in California, which meets one or more of the following conditions:

- Has annual gross revenues of more than $25m, or

- Buys, sells or shares data on more than 50,000 consumers per year, or

- Derives more than 50% of its revenue from selling consumers’ personal information.

This is noticeably narrower than GDPR, which includes in its scope any organization, including businesses, non-profits, and public sector entities (including governments).

The target of CCPA’s protections and rights are referred to as Consumers. A consumer is defined as a California resident. This is a narrower scope than GDPR, which covers all EU/EEA nationals, and anyone physically in the EU/EEA at the time of data collection. This means that while US businesses need to be GDPR-compliant if they have any users who are EU nationals (even if those individuals are in the US at the time their data is collected), the same is not true under CCPA – a Washington State resident on a visit to California (or using the services of a California-based business) is not protected under CCPA.

Definition of personal data

The definitions of personal data in the two laws are quite similar – they both cast a broad net in defining personal data as any data that can be connected to an individual. This means that the old idea of “Personally Identifiable Information” (PII) is largely obsolete – like GDPR, the law covers data like purchase history and website behaviour which would not have been considered PII previously.

CCPA does provide a provision that exempts ‘deidentified’ (anonymised) data – that is, data where identifiers (such as cookie IDs) have been removed. However, deidentification is a notoriously grey area – there are many examples of previously deidentified data being able to be linked back to individuals, such as the hospital admissions data that US states share publicly. CCPA says that simply removing explicit identifiers from a user data record is unlikely to be sufficient, because it would be unlikely to prevent reindentification.

CCPA also explicitly calls out “audio/electronic/visual/thermal/olfactory or similar information” as a category of data. This means that sensor data from IoT devices (e.g. smart lights, smart speakers) is covered by CCPA (looking at you, Google and Amazon).

Finally, while GDPR explicitly protects certain special categories of data such as health data, ethnicity, or religious affiliation by even stricter data processing rules, CCPA does not; however, it does make reference to other California and Federal laws (such as HIPAA and VPPA) which protect this kind of data explicitly.

Individuals’ rights

CCPA and GDPR share a similar focus on providing a core set of rights to consumers (‘Data Subjects’ in GDPR). They both provide the following rights to:

- Know what personal data is being held about them

- Access that data (data portability)

- Delete that data (right to be forgotten)

- Not be discriminated against (e.g. by reducing the quality of a service) for the exercise of any of the above rights

GDPR, on the other hand, provides its Data Subjects with further rights to:

- Require that their data is not used for certain purposes, such as targeted advertising

- Have incorrect data rectified

- Object to automated decision-making (e.g. automatic profiling)

Privacy notices and consent

CCPA requires businesses to notify consumers of the categories of data they are collecting, and the use(s) they are making of that data; if a business wants to change the data they are collecting, or the purposes they are using the data for, they must notify consumers. CCPA doesn’t require consent to be gathered for this data collection.

CCPA does have a specific consent clause to do with the sale of a consumer’s data to a third party – businesses must have a prominent link on their website home page titled “Do not sell my Personal Information”. This blanket opt-out is quite a good protection for consumers, while being quite manageable for businesses. For consumers between the ages of 13 and 16 years old, a business must gain an opt-in before sharing their data with third parties.

By contrast, GDPR requires organizations to gain opt-in consent from Data Subjects for most non-essential cases of data processing, including for purposes like digital marketing, and especially where data is to be shared with a third party. This need to gain pre-emptive consent for all potential uses of personal data is the reason behind the extremely complex and confusing consent management interfaces that have sprung up on websites.

Data retention and security

CCPA has nothing to say about the security measures that a business should take in order to protect the personal data that they are holding. It does, though, establish a ‘right of action’ for consumers who feel that a business has taken insufficient steps to protect their data in the event of a data breach. On the other hand, GDPR explicitly requires data controllers and data processors to take measures to secure personal data (such as encryption and/or anonymization).

CCPA also does not limit the amount of time that a business may retain personal data; under GDPR, data controllers are required to hold data for no longer than they need for the stated purpose for which they gathered it.

Enforcement and fines

Under CCPA, an accidental breach of the law attracts a fine of $2,500 per consumer affected. The fine rises to $7,500 per consumer record if the breach is considered deliberate.

By comparison, under GDPR, an organization can be fined between two and four percent of its total revenue for a breach, the range again reflecting the seriousness of the breach.

To get a sense of the likely impact of this, consider the example of Facebook, which famously shared profile data from 50 million of its users with Cambridge Analytica in 2014. Not all of these users were in California, but if just 5 million of them were, then Facebook could have faced a fine of between $12.5 and $37.5 billion. By comparison, an equivalent fine under GDPR could range from $1.1 to $2.2 billion, based on Facebook’s 2018 revenues (although its revenues in 2014 were a lot lower).

CCPA also provides an explicit range for the awards to be made to consumers who bring actions against companies who have breached CCPA with their data, of between $100 and $750 per user. If all 5 million consumers in the Facebook example had brought a class action against the company, the combined pay-out could have been as much as $3.75 billion. CCPA clearly has teeth.

CCPA, GDPR, oh my: Achieving compliance in a world of privacy laws

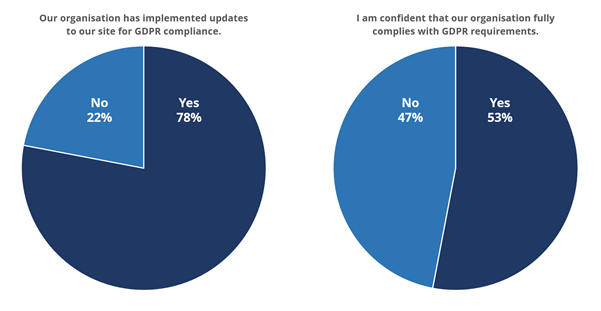

In early 2019, Ebiquity and the Digital Analytics Association (DAA) fielded a survey on US business readiness for GDPR. The responses were not tremendously encouraging: Although 78% of respondents said that their organizations had taken steps to achieve GDPR compliance, almost half (47%) were not confident that they’d done enough:

This lack of confidence reflects the fact that GDPR remains a confusing law, inconsistently applied by the different data protection agencies throughout the EU. Adding CCPA and other laws to the mix will only generate further confusion for beleaguered CDOs and CPOs who are just trying to do the right thing and stay out of trouble. What’s needed is an overall framework for thinking about privacy and risk when dealing with personal data.

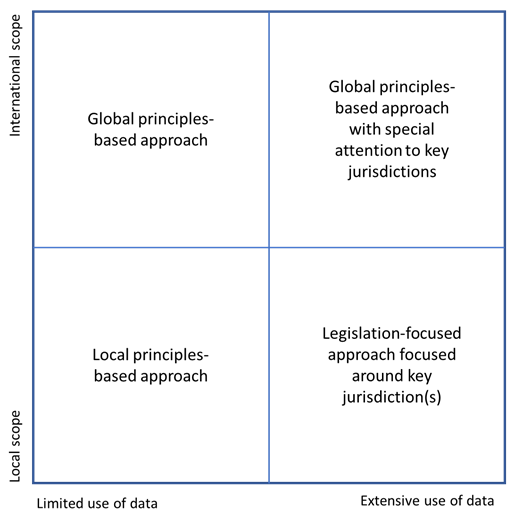

In practice, the amount of work that your organization needs to do to achieve compliance with global privacy legislation will depend on two major factors: Firstly, the extent to which the you have an international footprint, and secondly, the amount of use you’re making of personal data.

The diagram below provides a framework for thinking about the best approach to compliance as these two factors vary.

If you do most or all of your business in one or a few locations, you can comfortably focus just on the legislation that applies to your locale, although it is worth remembering that GDPR applies to all EU/EEA citizens whether or not they are in the EU, and that even within areas like the EU and USA, a patchwork of local laws will be applicable.

For international or multinational organizations, things are more complicated. As the range of laws continues to balloon, the most sensible approach is to establish a set of personal data management best practices which can be used as the foundation for legal compliance in any particular geography. If you fall foul of the law (e.g. through a data breach), you’re more likely to be viewed charitably by both consumers and regulators if your general practices around personal data management are sound and not seen as sloppy or evil.

The best practices below will put you in a good position to achieve compliance with both GDPR and CCPA – though I am not a lawyer, so you should not consider this legal advice:

Establish a set of principles for personal data usage

Before you do anything else, ask yourself what your core principles are for the collection and usage of personal data. Is it necessary for your business and marketing objectives, and if so, what is the minimum amount that will be sufficient for the task? The easiest way to minimise risk and management cost around personal data is to not collect it in the first place.

Treat all individual-level data as potentially sensitive

You need to treat all data at the individual level as potentially sensitive – in line with the GDPR definition. Anonymising or deidentifying personal data reduces the risk of a damaging breach, but does not eliminate it. Even aggregating personal data does not completely eliminate the risk that an individual record could be re-extracted.

Keep track of personal data collection and distribution

This foundational activity entails controlling the collection and storage of all personal data and then tracking and managing the movement of that data throughout your organization, ideally as part of a broader Master Data Management (MDM) program. You can achieve this by severely restricting access to personal data, but this can cause other problems (such as illicit copying and sharing of the data).

Maintain a clear data privacy statement

Your privacy statement needs to clearly state the categories of data that you’re collecting, and the purposes that they are being used for (CCPA provides some quite helpful categories to use for this). Obviously, this depends on the effective management of personal data collection and usage in the first place, per the previous point.

Keep track of data sharing with third parties

Related to the above, you need to keep detailed records of the third parties with whom you are sharing data, both through back-end data feeds and through third party data collection in digital properties such as websites and apps. You need to be able to turn those feeds on and off easily.

Limit duplication and movement of personal data

You need strong policies (and enforcement) around personal data are needed to prevent random Data Scientists in your team making copies of personal data and taking it home for the weekend. Again, a good Master Data Management system is very helpful here, since it can help reduce confusion about the location of the location of certain datasets. An MDM will also reduce data storage, movement and processing costs.

Limit data hoarding

Several privacy laws say that data should not be retained beyond a reasonable period. Just how long to hold onto personal data is a matter of choice, but don’t hold onto old data ‘just in case’ it might come in handy. A good rule of thumb is to expect to hold onto user-level personal data for no more than 12 months; beyond that, data should be aggregated (or at the very least deidentified/anonymised).

Store personal data securely

Storing data securely both reduces the chances of data breaches as well as reducing the likely penalties that you’ll have to pay if you do have a data breach. Encrypt your data, and aim to provide access only via data APIs, so that access can be logged and controlled. Also, anonymize your user IDs, so that if data is copied around the organization the risk of a damaging data breach is lessened.

Respond promptly to data subject requests

A common theme of both CCPA and GDPR is honouring requests from individuals to review, amend or delete the data that is being held about them. You need a robust process to respond to these requests, which will depend being able to locate where personal data is being stored. For example, if a user requests that their data be deleted, and there are multiple untracked copies of that data floating about, it will be very hard or impossible to honour this request.

Offer users meaningful control over data collection and sharing

This is one area where you might want to have different approaches in different markets. The EU takes an opt-in approach to gaining consent for data collection and processing, while the US leans towards opt-out (which is the approach taken by CCPA).

Since opt-in rates are always much lower than opt-out rates, there can be real benefit to taking advantage of the somewhat more permissive rules where they exist. But since laws will likely tighten over time, your consent tools need to be flexible enough to switch from opt-out to opt-in quickly. This is especially true for the controls you provide to manage the sharing of data with third parties.

Appoint a Chief Privacy Officer

Even though may privacy laws (including CCPA) don’t mandate it, you should appoint a Chief Privacy Officer. Your CPO needs to have real power – they must be able to direct resources to build systems that will facilitate the management of personal data and to respond to data subject requests, and should also be independent from the marketing organization so that they can dispassionately assess the privacy risks associated with the collection and use of personal data.

Thank you for sharing.